Slow-Cooked Tender Lamb Mansaf

Hospitality as a Human Virtue

The Mansaf Manifesto: An Edible History of a Geopolitical Triumph and Kinship

What is Mansaf all about? How does Mansaf function as:

· Achronicle of sovereignty,

· A social institution,

· A marker of national heritage in Jordan and Palestine?

In fact, Mansaf is a geopolitical memoir, an archive of resilience written in rice, lamb, and jameed. To contemplate Mansaf is to engage with the very soul of the Levant, transcending the commercial or the fleeting to embrace a huge cultural inheritance. This dish serves as an edible testimony, a sacred text prepared in the kitchen of Teta (grandmother), whose wisdom and generosity become the ultimate custodians of historical and cultural fidelity.

The Genesis of Jameed: A 7,000-Year-Old Act of Identity

The origins of Mansaf are a layered tapestry, weaving together ancient agricultural roots with defining political acts. Scientific archaeology indicates that the dish's fundamental elements—lamb, fermented dairy, and communal feasting—were present in the fertile lands of ancient Jordan as early as 5000–6500 B.C. Excavations at sites like 'Ain Ghazal, near modern Amman, reveal a profound reliance on domesticated goats and sheep. The prevalence of these bones (up to 95% of finds) confirms the abundant availability of the raw materials for both the meat and the foundational jameed—a to the deconstructed dairy of our contemporary diet. This truth anchors Mansaf not in transient fashion, but in the enduring cycle of the earth and the early Levantine agricultural societies.

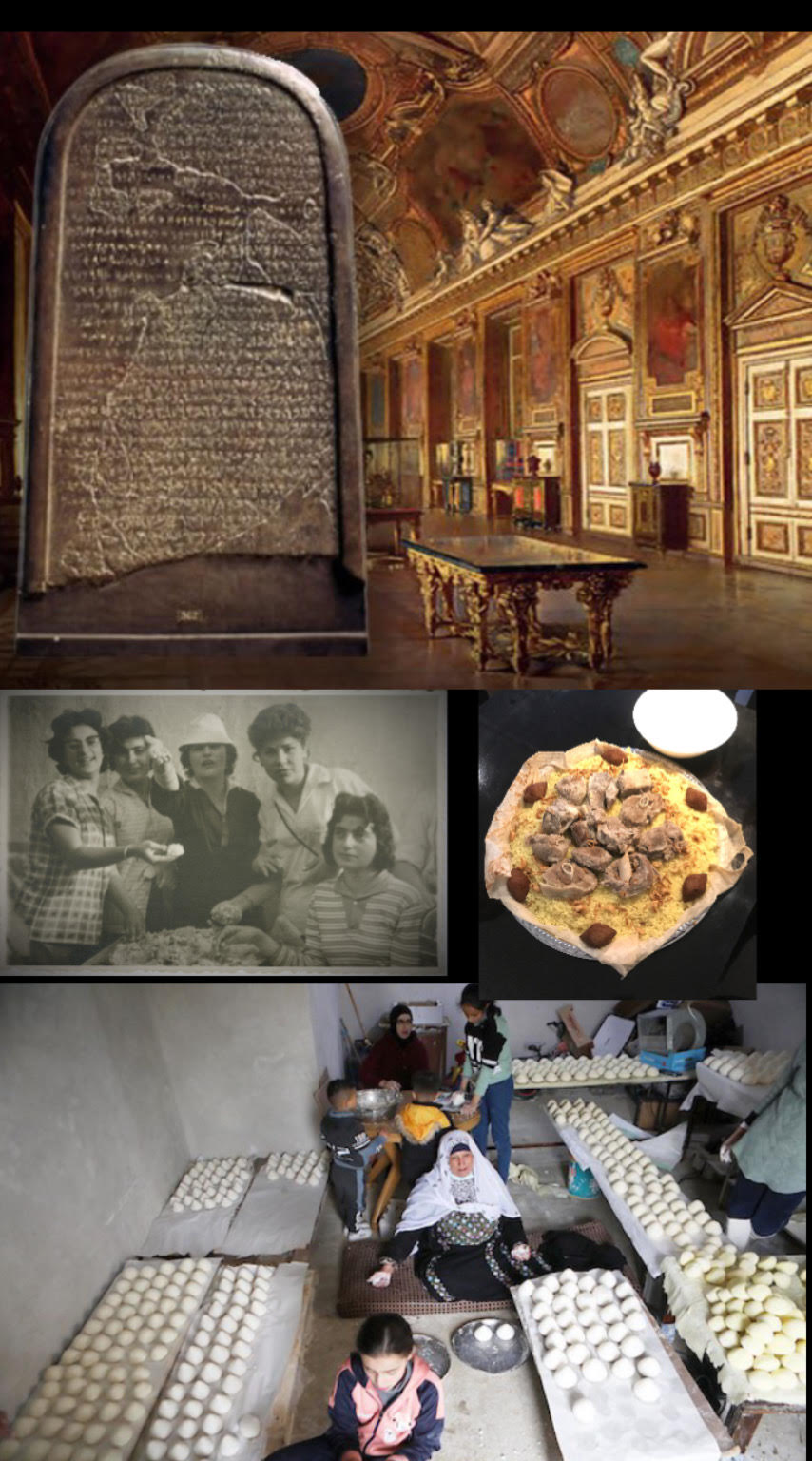

The historical genesis of Mansaf, around 3,200 years ago during the Moabite Kingdom, serves as a powerful testament to the dish's enduring political significance. The popular narrative holds that King Mesha successfully weaponised gastronomy, transforming a simple meal into an instrument of democratic referendum and national screening!

The Context of Defiance

The relationship between the Moabite Kingdom and the Hebrews was marked by cycles of conflict and fragile truces. When Mesha discovered that the Hebrews were preparing to betray the ceasefire and seize lands west of the Jordan River through treachery, he mobilised for a decisive war.

However, this existential conflict demanded absolute commitment. To gauge the loyalty and readiness of his populace, Mesha devised a visceral test rooted in the opposing culture's core dogma:

The Divine Prohibition: The Israelite creed, documented in the Torah (Exodus 23:19), strictly forbade lamb cooked in yogurt.

The Royal Command: Mesha issued a decree commanding his people to cook meat in yogurt.

An Act of Sovereignty and Separation

This command was a visceral litmus test of loyalty designed to separate the committed Moabite from any potential collaborator or infiltrator. By publicly embracing the preparation of this forbidden dish, the Moabites collectively affirmed their identity and their total commitment to the forthcoming military struggle, which led at the end to the victory of Moabites.

This triumph—a victory secured through both militaries might and a brilliant act of cultural and political distinction—was immortalised by Mesha on the Mesha Stele, which now resides in the Louvre Museum.

Thus, Mansaf became inextricably linked to victory, dignity, and the very identity of the Jordanian people. It is a dual heritage born of the earth, baptised in political courage.

The Sadr Al-Karam: The Geometry of Communal Ethics

The physical presentation of Mansaf is a philosophical statement. The food is served on a Sedr (سدر)—a large, broad platter, whose archaeological echo can be found in the vast serving bowls unearthed at ancient sites in Jordan and in Palestine. This shared canvas negates individualism; the act of eating is communal, a ceremony of participation, when the absence of personal plates forces proximity and fellowship.

This gathering is not merely functional; it is codified by honour and tradition:

The Right Hand: Eating is performed strictly with the right hand, shaping the rice and lamb into small, respectful(balls).

The Host's Custody: The host performs the crucial, silent ritual of pouring the melted samneh (ghee) and the jameed broth, acting as a steward of sustenance and honour.

The Head of Honour: The placement of the whole sheep’s head signifies profound respect for the most honoured guests, and the careful observation of the meat’s arrangement is a social obligation.

The Unseen Base: Guests are enjoined not to reveal the base of the Sedr, a symbolic gesture ensuring the spirit of abundance and generosity is maintained.

In this communal act, Mansaf becomes an active agent of social cohesion—a profound ethical framework where the sharing of resources is the highest form of virtue, cementing bonds that transcend mere acquaintance.

The Eternal Embrace: A Feast for the Soul of Palestine

While its roots are agricultural, Mansaf has been passionately adopted and redefined by the Palestinian cultural landscape, particularly among Bedouin and rural communities, where the traditions of pastoralism and generosity are most acute. For Palestinians, Mansaf is the unifying axis of life's pivotal moments—a dish that travels between the West Bank and Jordan, indifferent to geopolitical lines.

The dish is the essential anchor for:

The Wedding Feast: Marking the genesis of a new family and alliance.

National and Social Celebrations: Serving as the gastronomic banner for events of collective pride and unity.

The Ramadhan Iftar: Gathering relatives from near and far, weaving bridges of connection through the shared memory of home and heritage.

Conflict Resolution: It is the final, tangible sign of peace, offered when disputes are resolved and harmony is restored.

In the hands of the Palestinian grandmother (Teta), Mansaf becomes a sacrament of eternity.

Hospitality, within the Palestinian national traditions, is considered not merely as a social convention but as a fundamental ethical posture. It marks the intimate insistence on shattering the barriers that separate the interior and the external world. The act of opening one’s abode is, at its core, an act of existential courage – a defiant negation of enclosure.

It is the signature of a boundless moral cartography, extending an ultimate willingness of unreserved welcome. This singular gesture manifests the purest form of a universalist creed, a humanity unbound by spatial or conventional limits.

The River of the Levant: A Unity Transcending Borders

The final, philosophical truth of Mansaf is its designation as a shared cultural river between the two banks of the Levant: The West Bank and Jordan. Though politically divided, the aroma, texture, and flavour of the dish meet and merge, forming a seamless tapestry of identity.

The slow-cooked lamb and tangy jameed are the intertwined veins of a single, shared history.

It is a cultural current enriched with collective dreams, sorrows, and the enduring hope of the region.

This shared heritage transforms the meal into a sanctuary—impervious to the haste of modern commerce and the hollow immediacy of fast food. Mansaf demands presence, attention, and reverence; it is a moral compass and an edible testament to a people who honour their past, their land, and one another. Every shared bite whispers the story of an enduring unity, a silent declaration that the heart of the Levant beats as one.