Palestinian Freekeh

Land’s wheat-toned face

Freekeh: The Wheat of Identity, The Fire of Resurrection

Freekeh, the ancient Palestinian dish, the original narrative of identity, land, and cultural redemption, etched into the roasted grains of green wheat. This dish weaves a spiritual tapestry, connecting the Palestinian soul to the depth of its agricultural history, standing as a living testament to cultural resilience and the power of memory, and loyalty to the deep rootedness of the Palestinian rituals.

The Sun-Kissed Skin and The Wheat’s Mirror: Embodied Identity

The Palestinian self is conceptually born from the fields. The description of one’s being becomes an echo of the environment: "This is our face — the wheat-toned warmth kindled by the sun and the sweat of the fields. We emerge from golden grains of wheat; they are our mirrors, and our faces are their reflection, reflecting the fields and threshing grounds themselves." This is not mere poetic description of complexion; it is a declaration of Absolute Belonging. The skin is an extension of the soil, and identity is the land that resembles the people and is, in turn, resembled by them.

In this sphere, the Palestinian grandmother transcends the role of homemaker. She is the "goddess of the table, mistress of the hearth, and guardian of the feast," the sacred carrier of the wheat’s wisdom. Through her hands, the grain becomes more than sustenance; it is transformed into identity — "the living spirit of a nation, a golden thread linking the land to its native people."

The Fire of Sacrifice: A Masterclass in Cultural Rescue

At the heart of Freekeh’s creation lies a deeper story of cultural sacrifice and the ingenuity of grandmothers, the silent "cultural rescue engineers." Historical accounts suggest that charring the green wheat heads was not merely a farming technique, but a desperate, creative act to save the crop from invading forces. Before an occupier could seize and steal the young, vital harvest, the grandmother would choose to torch the field, thereby hiding the essence of the crop within the protective ash, rendering it inedible to the invaders yet preserved for her family.

From this ritual of fire, an authentic, smoky flavour is born, along with a powerful symbol of resilience. It is the philosophy of "Resurrection" made tangible: igniting the immediate existence to preserve the enduring spirit, where the fire becomes an instrument of preservation, not destruction.

The Sublime Grain: A Superior and Authentic Staple

Freekeh holds court at the Palestinian table, reigning as a timeless dish, embodying the bliss of the land and the depth of our belonging. It serves as a superior, deeply flavourful, and authentic alternative to rice. The lightly roasted green wheat offers significantly higher nutritional value, along with an unparalleled smoky, nutty flavour that recalls the aroma of harvest seasons that breathe life into the fields and threshing grounds.

The Craft of Creation: A Ritual of Harvest and Flame

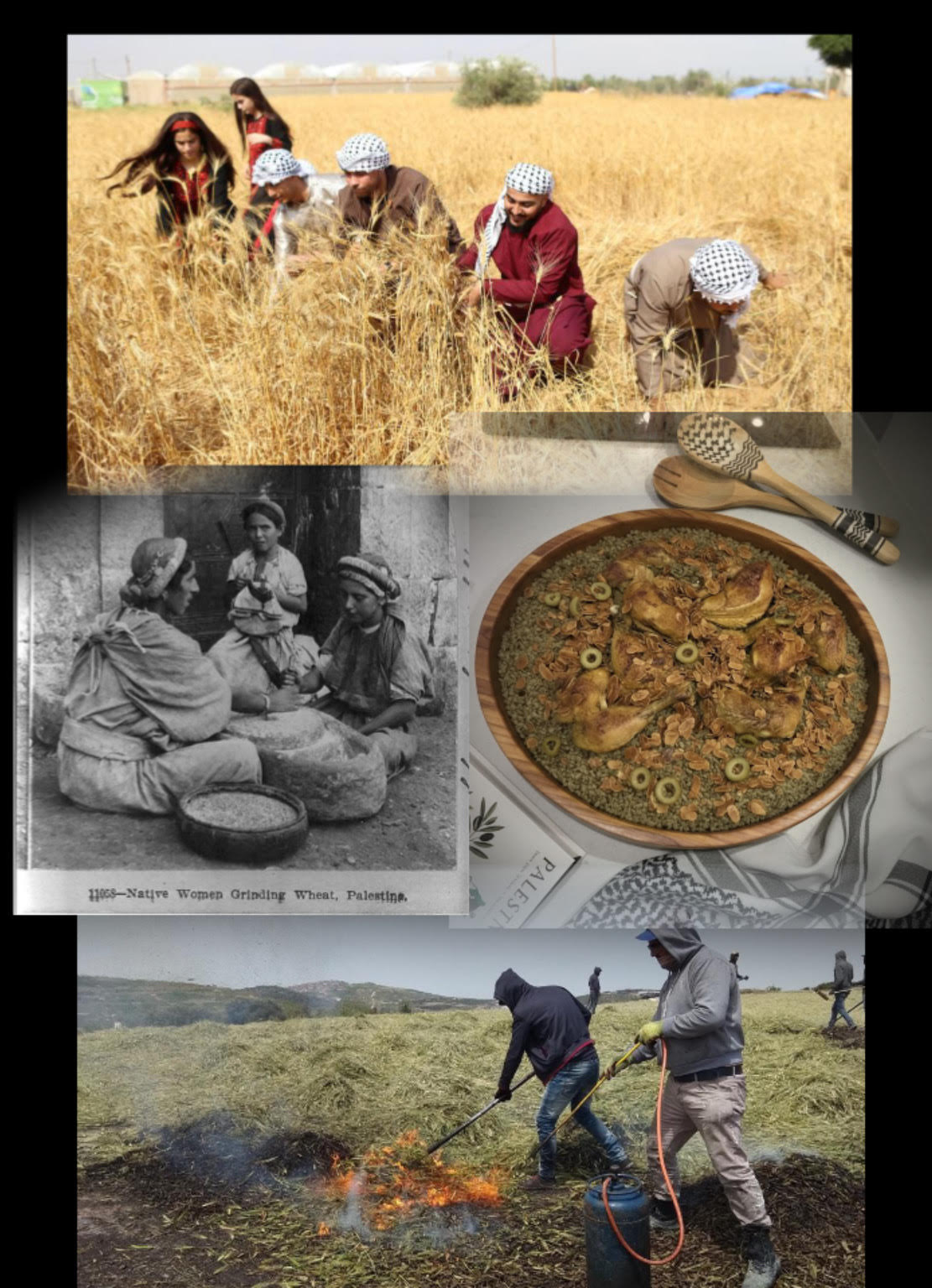

The making of Freekeh is a beautiful social ritual. The process begins by scattering the fresh, green wheat heads on the threshing floor (the Baydar), allowing them to sun-dry for approximately two hours.

The charring process then commences, which is both the most dramatic and philosophical element:

The Firing (The Philosophical Flame): The unripe wheat is roasted using flames, traditionally from dry wood or, more recently, jets of fire from gas canisters. The crucial role of fire here is to provide life from the ashes.

Turning Amidst the Blaze: The wheat heads are continuously and carefully turned with special tools to ensure they are evenly roasted and smoked without being fully consumed. This fertile scene, often taking place in the spring and involving "living amidst the fire," is the very embodiment of ordeal and rebirth.

Threshing and Sifting: Once charred, the wheat heads are threshed (rubbed) to separate the smoky grains from the chaff and ash through winnowing. The name itself, "Freekeh," derives from the Arabic verb faraka, meaning to rub or to separate.

Ancient Roots: The Endurance of Wheat

Agricultural experts and archaeological evidence firmly establish the deep antiquity of wheat cultivation in the Levant:

Mesolithic Era: Wheat and cereals were known to be cultivated in Palestine and the Levant since the Mesolithic period, extending from roughly 12,000 BCE.

Archaeological Evidence: The Dutch archaeologist Henri Frankfort noted in The Birth of Civilization in the Near East that the wild ancestors of wheat and barley still exist in Syria and Palestine, and that the art of harvesting developed in this region from time immemorial.

The Natufians: In the caves of the Carmel Mountains, remains were discovered of the earliest people to use sickles—the Natufians (named after Wadi Natuf, northwest of Ramallah). They pioneered the art of harvesting with unique sickles composed of a notched bone handle containing short flint segments, like teeth.

Though Freekeh’s history is lengthy, we can confine it within a single banner heading that carries its most philosophical dimensions and readings:

Born from the green-gold fields, Freekeh is the precious jewel of Jenin...It is the story of a humble grain transformed into a dish steeped in the wisdom and fertile spirit of the land.

Reference and Attribution: This account draws upon documentation, notably from the "AFAQ Environmental and Development" website, which in turn referenced an article published in the Palestine Newspaper in 1930 concerning the harvest season and flint sickles: https://www.maan-ctr.org/magazine/article/3838/